巴菲特致股東函 2018

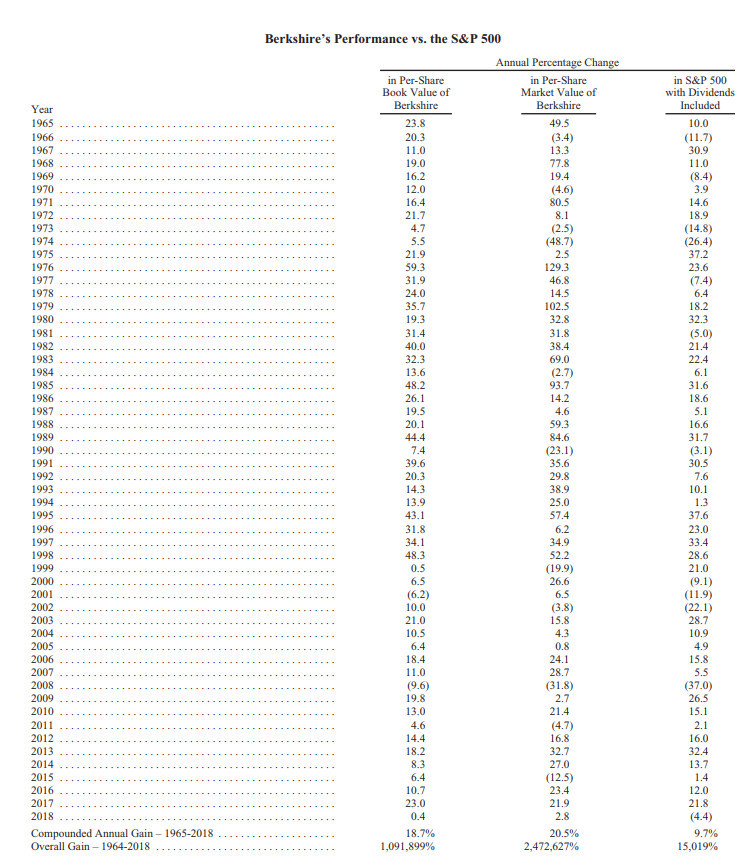

Note: Data are for calendar years with these exceptions: 1965 and 1966, year ended 9/30; 1967, 15 months ended 12/31. Starting in 1979, accounting rules required insurance companies to value the equity securities they hold at market rather than at the lower of cost or market, which was previously the requirement. In this table, Berkshire’s results through 1978 have been restated to conform to the changed rules. In all other respects, the results are calculated using the numbers originally reported. The S&P 500 numbers are pre-tax whereas the Berkshire numbers are after-tax. If a corporation such as Berkshire were simply to have owned the S&P 500 and accrued the appropriate taxes, its results would have lagged the S&P 500 in years when that index showed a positive return, but would have exceeded the S&P 500 in years when the index showed a negative return. Over the years, the tax costs would have caused the aggregate lag to be substantial.

To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

波克夏·海瑟威的各位股東們好:

Berkshire earned $4.0 billion in 2018 utilizing generally accepted accounting principles (commonly called “GAAP”). The components of that figure are $24.8 billion in operating earnings, a $3.0 billion non-cash loss from an impairment of intangible assets (arising almost entirely from our equity interest in Kraft Heinz), $2.8 billion in realized capital gains from the sale of investment securities and a $20.6 billion loss from a reduction in the amount of unrealized capital gains that existed in our investment holdings.

波克夏·海瑟威的各位股東們好:

Berkshire earned $4.0 billion in 2018 utilizing generally accepted accounting principles (commonly called “GAAP”). The components of that figure are $24.8 billion in operating earnings, a $3.0 billion non-cash loss from an impairment of intangible assets (arising almost entirely from our equity interest in Kraft Heinz), $2.8 billion in realized capital gains from the sale of investment securities and a $20.6 billion loss from a reduction in the amount of unrealized capital gains that existed in our investment holdings.

2018年當中,波克夏的通用會計準則(GAAP)盈利總計為40億美元。具體而言,這當中包括248億美元運營盈利,30億美元源於無形資產受損的非現金虧損(幾乎全部來自卡夫亨氏的持股),28億美元的來自已售出投資證券的兌現資本利得,以及206億美元的“虧損”,後者是來自我們依然持有的投資的未兌現資本利得減少。

A new GAAP rule requires us to include that last item in earnings. As I emphasized in the 2017 annual report, neither Berkshire’s Vice Chairman, Charlie Munger, nor I believe that rule to be sensible. Rather, both of us have consistently thought that at Berkshire this mark-to-market change would produce what I described as “wild and capricious swings in our bottom line.”

根據新GAAP規則的要求,我們必須將這最後一項納入我們的盈利數據。正如我在2017年財報當中所強調過的,無論是波克夏的副董事長孟格(Charlie Munger),還是我本人都覺得這種規則是沒有道理的,相反,在我們看來,對於波克夏而言,這種要求逐日盯市的改變只能造成我所謂的“我們盈利的狂野而變化無常的震蕩”。

The accuracy of that prediction can be suggested by our quarterly results during 2018. In the first and fourth quarters, we reported GAAP losses of $1.1 billion and $25.4 billion respectively. In the second and third quarters, we reported profits of $12 billion and $18.5 billion. In complete contrast to these gyrations, the many businesses that Berkshire owns delivered consistent and satisfactory operating earnings in all quarters. For the year, those earnings exceeded their 2016 high of $17.6 billion by 41%.

事實上,我們2018年每個季度的財報可以說都在證明我這種預言的準確性。比如,在第一和第四季度當中,我們分別報告了11億美元和254億美元的GAAP“虧損”。第二和第三季度,我們又分別報告了120億美元和185億美元的“利潤”。然而在現實層面,波克夏旗下的諸多企業 “全部”四個季度當中,其實都交付出了具有持續性的,令人滿意的運營盈利。就這一年全年而言,這種盈利在2016年的176億美元高點上又前進了41%。

事實上,我們2018年每個季度的財報可以說都在證明我這種預言的準確性。比如,在第一和第四季度當中,我們分別報告了11億美元和254億美元的GAAP“虧損”。第二和第三季度,我們又分別報告了120億美元和185億美元的“利潤”。然而在現實層面,波克夏旗下的諸多企業 “全部”四個季度當中,其實都交付出了具有持續性的,令人滿意的運營盈利。就這一年全年而言,這種盈利在2016年的176億美元高點上又前進了41%。

Wide swings in our quarterly GAAP earnings will inevitably continue. That’s because our huge equity portfolio – valued at nearly $173 billion at the end of 2018 – will often experience one-day price fluctuations of $2 billion or more, all of which the new rule says must be dropped immediately to our bottom line. Indeed, in the fourth quarter, a period of high volatility in stock prices, we experienced several days with a “profit” or “loss” of more than $4 billion.

我們每個季度的GAAP盈利的狂野波動必然還將繼續下去。這是因為我們投資組合的規模龐大——截至2018年底,價值近1730億美元,一天之內就縮水或者膨脹20億美元乃至更多,完全是家常便飯,但是新規則卻要求我們將這種變化當即落實到我們的盈利數字當中。事實就是,在去年第四季度那段股價波動極端劇烈的時期,我們至少有七天的“利潤”或者“虧損”都超過了40億美元。

我們每個季度的GAAP盈利的狂野波動必然還將繼續下去。這是因為我們投資組合的規模龐大——截至2018年底,價值近1730億美元,一天之內就縮水或者膨脹20億美元乃至更多,完全是家常便飯,但是新規則卻要求我們將這種變化當即落實到我們的盈利數字當中。事實就是,在去年第四季度那段股價波動極端劇烈的時期,我們至少有七天的“利潤”或者“虧損”都超過了40億美元。

Our advice? Focus on operating earnings, paying little attention to gains or losses of any variety. My saying that in no way diminishes the importance of our investments to Berkshire. Over time, Charlie and I expect them to deliver substantial gains, albeit with highly irregular timing.

如果各位股東要問我們能夠提供什麽建議,回答是,大家最好專注於運營盈利,不要去在意任何其他一種利得或者虧損。我要說的是,大家對波克夏的投資的重要性不會因為量度的變化而有實質性的改變。長期而言,查理和我預計這些投資都將貢獻出持續的利得——儘管在不同的時間節點,它們看上去可能會很怪異。

如果各位股東要問我們能夠提供什麽建議,回答是,大家最好專注於運營盈利,不要去在意任何其他一種利得或者虧損。我要說的是,大家對波克夏的投資的重要性不會因為量度的變化而有實質性的改變。長期而言,查理和我預計這些投資都將貢獻出持續的利得——儘管在不同的時間節點,它們看上去可能會很怪異。

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Long-time readers of our annual reports will have spotted the different way in which I opened this letter. For nearly three decades, the initial paragraph featured the percentage change in Berkshire’s per-share book value. It’s now time to abandon that practice.

長期關注我們年報的人們可能已經發現,這一封股東信的開篇和許多往年都有所不同。在長達近三十年的時間當中,我們在最初的段落裡都是主要談論波克夏每股帳面價值的變化。可是現在,我們是時候改弦更張了。

The fact is that the annual change in Berkshire’s book value – which makes its farewell appearance on page 2 – is a metric that has lost the relevance it once had. Three circumstances have made that so. First, Berkshire has gradually morphed from a company whose assets are concentrated in marketable stocks into one whose major value resides in operating businesses. Charlie and I expect that reshaping to continue in an irregular manner. Second, while our equity holdings are valued at market prices, accounting rules require our collection of operating companies to be included in book value at an amount far below their current value, a mismark that has grown in recent years. Third, it is likely that – over time – Berkshire will be a significant repurchaser of its shares, transactions that will take place at prices above book value but below our estimate of intrinsic value. The math of such purchases is simple: Each transaction makes per-share intrinsic value go up, while per-share book value goes down. That combination causes the book-value scorecard to become increasingly out of touch with economic reality.

事實就是,波克夏帳面價值的年度變化——在第二頁會和大家做一個告別——作為一個指標而言,已經不再像過去那樣至關重要了。這是環境的變化使然。首先,波克夏已經逐漸蛻變,從一家全部資產主要集中於可銷售股票當中的公司變化為一家主要價值來自於運營業務的公司。查理和我估計,這種公司的重塑將以一種不規則的方式繼續下去。其次,當下的會計準則儘管要求我們將持有的股票逐日盯緊市場來定價,但是對我們的運營企業,卻要求其以遠低於當前價值的帳面價值來入帳,這種錯誤的影響近年以來變得日益嚴重。第三,從長期角度看來,波克夏很可能會成為一個自身股票的重量級回購者,當股票價格高於帳面價值而又低於我們估計的內在價值時,回購就會發生。這種回購背後的計算邏輯非常簡單——每一筆交易都會使得每股內在價值提高,同時使得每股帳面價值降低。兩者交相作用,就會使得記錄在案的帳面價值日益遠離我們的經濟現實。

In future tabulations of our financial results, we expect to focus on Berkshire’s market price. Markets can be extremely capricious: Just look at the 54-year history laid out on page 2. Over time, however, Berkshire’s stock price will provide the best measure of business performance.

在波克夏未來的財務業績報告當中,我們預計會專注於其市場價格。市場完全可能是極端反覆無常的——看看我們第二頁列出的54年歷史記錄,大家就會有一個最直觀的印象。不過,若是著眼於長期,波克夏的股價確實是我們業務表現的最佳指標。

* * * * * * * * * * * *

在繼續下面的內容之前,我首先要報告給大家一些好消息,“實實在在”的好消息,是我們的財務報告無法體現的。具體來說就是和我們2018年初的管理層調整有關,賈因(Ajit Jain)被授權負責我們所有的保險業務,而艾貝爾(Greg Abel)則負責整體運營。其實,這樣的任命早就該下達了。波克夏現在的管理情況要比我獨自一人總攬全域時好了很多。這兩位都是罕見的天才,而且血液中深深烙印著波克夏的DNA。

Now let’s take a look at what you own.

下面我們就來看看各位的收獲。

Focus on the Forest – Forget the Trees

放眼森林——忘記獨木

Investors who evaluate Berkshire sometimes obsess on the details of our many and diverse businesses – our economic “trees,” so to speak. Analysis of that type can be mind-numbing, given that we own a vast array of specimens, ranging from twigs to redwoods. A few of our trees are diseased and unlikely to be around a decade from now. Many others, though, are destined to grow in size and beauty.

實話實說,那些汲汲於評估波克夏的價值的投資者經常會忽略掉我們為數眾多且各不相同的多種業務,即我們的經濟“森林”。誠然,我們旗下的這些企業令人目不暇接,要予以明確分析著實是一件令人頭痛的差事。這些樹木當中也有一些罹患疾病,可能未來十年都難見開花結果,但是許多其他植株,卻肯定會長成參天大樹,呈現出超乎大家意料的壯美。

幸運的是,對於想要粗略估計波克夏內在企業價值的諸君而言,大家不必對每一棵樹木都瞭若指掌。這是因為我們的森林包括了五個主要的“樹叢”,每一個都能夠有一個大致準確的整體評估。這五個樹叢當中有四個,從業務和金融資產的角度看來都和其他的差別明顯,這是大家都很容易理解的,而第五個,即我們龐大而複雜的保險業務,則以一種不那麽顯而易見的方式為整個波克夏奉獻著巨大的價值,在後文當中,我還將繼續為大家做出更詳盡的解釋。

Before we look more closely at the first four groves, let me remind you of our prime goal in the deployment of your capital: to buy ably-managed businesses, in whole or part, that possess favorable and durable economic characteristics. We also need to make these purchases at sensible prices.

在我們更近距離地觀察這前四個樹叢之前,首先要提醒大家,我們的首要目標就是要有效配置我們的資本——購買管理巧妙的企業,後者必須是在部分或者整體的層面,具備良好和可持久的經濟特質。當然,這種收購的價格也必須是合情合理的。

有些時候,我們能夠通過收購獲得符合我們標準的企業的控制權。可是,在更多的其他時候,我們會在許多上市公司身上發現我們尋求的特質,而我們一般會收購其5%到10%的股份。我們這種雙管齊下的超大規模資本配置操作在美國企業界也是很罕見的,這有些時候也會讓我們獲得重要的優勢。

近年以來,我們越來越清楚地認識到自己該採用怎樣一種合理的方式——許多上市公司的總市值決定了我們要整體收購他們,在資金上根本是不可能的。這種差異之下,我們去年購入了大約430億美元的可銷售股票,同時只賣掉了190億美元。查理和我相信,我們所投資的企業具有非凡的價值,遠遠超過那些可以整體收購的選項。

儘管我們近期加大力度購入了諸多可銷售股票,波克夏森林當中最有價值的樹叢依然是我們所控制的(往往都是100%控股,至少也不少於80%)的幾十上百家非保險企業。這些子公司去年為我們賺取了168億美元的盈利。值得一提的是,這裡所謂的“賺取”,還是指扣除了“所有”稅項、利息、管理層薪酬(無論股票或者現金)、重組支出、折舊、攤銷和行政費用之後的淨數字。

That brand of earnings is a far cry from that frequently touted by Wall Street bankers and corporate CEOs. Too often, their presentations feature “adjusted EBITDA,” a measure that redefines “earnings” to exclude a variety of all-too-real costs.

這一定義與華爾街銀行家和一些CEO們常常兜售的概念相去甚遠。他們通常會使用“調整後的EBITDA”,這種方法把一些應當計入的成本排除在外。

For example, managements sometimes assert that their company’s stock-based compensation shouldn’t be counted as an expense. (What else could it be – a gift from shareholders?) And restructuring expenses? Well, maybe last year’s exact rearrangement won’t recur. But restructurings of one sort or another are common in business – Berkshire has gone down that road dozens of times, and our shareholders have always borne the costs of doing so.

比如,企業界有些時候會認為,自己公司基於股票的薪酬不該被計為支出。(可是那又該怎麽落賬,難道算成股東給他們的禮物?)重組支出?也許那只是去年特定的項目,不會重復出現——可事實上,重組對企業而言是家常便飯,就波克夏自己,這一路走來就不知道有幾十次了,而每一次歸根結底都要靠我們的股東來埋單。

林肯(Abraham Lincoln)曾經有一個著名的質問:“如果你把狗尾巴也算作是一條腿,那麽一隻狗到底有幾條腿?”接下來,他自問自答:“四條,因為就算你說尾巴是腿,也不會使它真正變成腿。”看來,如果林肯要混華爾街,日子肯定好過不了。

Charlie and I do contend that our acquisition-related amortization expenses of $1.4 billion (detailed on page K-84) are not a true economic cost. We add back such amortization “costs” to GAAP earnings when we are evaluating both private businesses and marketable stocks.

查理和我一直都主張,我們收購相關的14億美元攤銷支出(詳情參見K-84)其實並不該視為真正的經濟成本。只不過,在我們估算自營企業和可銷售股票的價值時,還是不能不將這些攤銷“成本”列入到GAAP盈利當中。

In contrast, Berkshire’s $8.4 billion depreciation charge understates our true economic cost. In fact, we need to spend more than this sum annually to simply remain competitive in our many operations. Beyond those “maintenance” capital expenditures, we spend large sums in pursuit of growth. Overall, Berkshire invested a record $14.5 billion last year in plant, equipment and other fixed assets, with 89% of that spent in America.

與此形成鮮明對比的是,波克夏的84億美元折舊支出則是低估了真正的經濟成本。事實上,我們許多旗下業務要保持競爭力,需要投入的真實年度開支總額是要超過這個數字的。除了這些“維護”資本支出之外,我們還必須大力投入,尋求成長。整體而言,波克夏去年在廠房、設備和其他固定資產方面的投資達到了創紀錄的145億美元,其中89%是在美國本土進行。

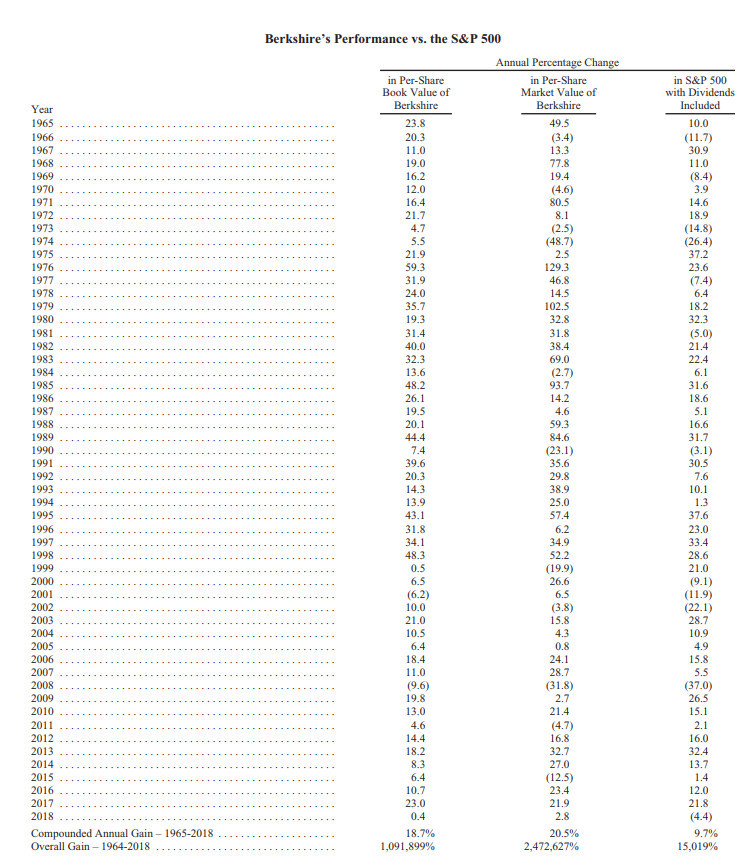

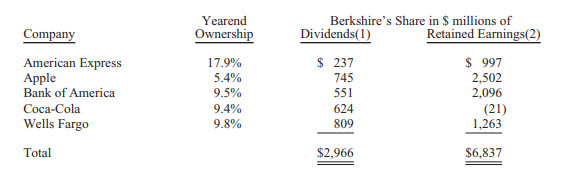

Berkshire’s runner-up grove by value is its collection of equities, typically involving a 5% to 10% ownership position in a very large company. As noted earlier, our equity investments were worth nearly $173 billion at yearend, an amount far above their cost. If the portfolio had been sold at its yearend valuation, federal income tax of about $14.7 billion would have been payable on the gain. In all likelihood, we will hold most of these stocks for a long time. Eventually, however, gains generate taxes at whatever rate prevails at the time of sale.

波克夏以價值論排名第二的樹叢,是我們所收集的股票,一般都是購入許多大型公司5%到10%的股權。如前文所說,我們的股票投資總價值到去年年底已經接近1730億美元,遠遠超過了最初的投入。如果這整個投資組合以去年年底的價格售出,我們單單聯邦所得稅就要繳納大約147億美元。不必說,在正常情況之下,我們都會將這些股票堅持持有很長的時間。只是,我們最終售出時,總歸要引發稅負,差別只在當時的稅率是多少。

去年,我們的投資為我們奉獻了38億美元的股息,這一收入的總額2019年預計還會增加。只不過,和股息相比,其實這些公司各自保留的年度盈餘要重要得多。要知道這個指標的情況,看看我們五個最大投資對象的情況就可以有個初步瞭解。

(2) Based on 2018 earnings minus common and preferred dividends paid. (2) 基於2018年盈利扣除普通股和優先股股息的數字

GAAP – which dictates the earnings we report – does not allow us to include the retained earnings of investees in our financial accounts. But those earnings are of enormous value to us: Over the years, earnings retained by our investees (viewed as a group) have eventually delivered capital gains to Berkshire that totaled more than one dollar for each dollar these companies reinvested for us.

我們當前所報告的盈利必須基於GAAP原則,後者不允許我們將投資對象的保留盈利計入我們的財務數據。可是,這些盈利對於我們卻有著巨大的價值——長期而言,作為一個整體,我們投資對象所保留的盈利最終將為波克夏創造出極為可觀的資本利得,今天他們再投資的一美元,未來帶給我們的將遠超過一美元。

All of our major holdings enjoy excellent economics, and most use a portion of their retained earnings to repurchase their shares. We very much like that: If Charlie and I think an investee’s stock is underpriced, we rejoice when management employs some of its earnings to increase Berkshire’s ownership percentage.

從經濟視角看來,我們的所有主要持股都可圈可點,這些企業都在使用自己保留的一部分盈利回購自家的股票。我們非常樂於看到這一幕:如果查理和我覺得投資對象股票的價格被低估了,而管理層又決定動用一部分保留盈利來提升波克夏持股相應的所有權百分比時,我們會開心地慶祝起來的。

Here’s one example drawn from the table above: Berkshire’s holdings of American Express have remained unchanged over the past eight years. Meanwhile, our ownership increased from 12.6% to 17.9% because of repurchases made by the company. Last year, Berkshire’s portion of the $6.9 billion earned by American Express was $1.2 billion, about 96% of the $1.3 billion we paid for our stake in the company. When earnings increase and shares outstanding decrease, owners – over time – usually do well.

下面是從上表中舉出的一個例子:波克夏對美國運通的持股量在過去八年時間裡一直都保持不變。與此同時,由於該公司回購了股票,因此我們的持股比例從12.6%上升到了17.9%。去年,在美國運通賺到的69億美元中,波克夏分到了12億美元,在我們為收購該公司股票而支付的13億美元中佔到了96%左右。當盈利增長且在外流通股票總量減少時,股票持有者——隨著時間的推移——通常會有良好的表現。

A third category of Berkshire’s business ownership is a quartet of companies in which we share control with other parties. Our portion of the after-tax operating earnings of these businesses – 26.7% of Kraft Heinz, 50% of Berkadia and Electric Transmission Texas, and 38.6% of Pilot Flying J – totaled about $1.3 billion in 2018.

波克夏擁有的第三類企業是我們與其他各方共用控制權的四家公司。2018年中,我們在這些企業的稅後營業利潤中所佔份額——卡夫亨氏為26.7%、Berkadia和得州電力傳輸公司均為50%,Pilot Flying J為38.6%——總計約為13億美元。

In our fourth grove, Berkshire held $112 billion at yearend in U.S. Treasury bills and other cash equivalents, and another $20 billion in miscellaneous fixed-income instruments. We consider a portion of that stash to be untouchable, having pledged to always hold at least $20 billion in cash equivalents to guard against external calamities. We have also promised to avoid any activities that could threaten our maintaining that buffer.

第四類則是,截至年底為止波克夏持有價值1120億美元的美國國庫券和其他現金等價物,另有200億美元的雜項固定收益工具。我們認為,這些儲備中有一部分是不可動的,承諾始終會持有至少200億美元的現金等價物以防範外部災難。我們還承諾將避免任何可能威脅到我們維持這種緩衝的活動。

Berkshire will forever remain a financial fortress. In managing, I will make expensive mistakes of commission and will also miss many opportunities, some of which should have been obvious to me. At times, our stock will tumble as investors flee from equities. But I will never risk getting caught short of cash.

波克夏永遠都將保持一個金融堡壘的身份。在管理方面,我會犯代價高昂的委任錯誤,也會錯失許多機會,其中一些機會對我來說原本該是顯而易見的。有些時候,隨著投資者逃離股市,我們的股價會大幅下挫。但我永遠都不會冒現金短缺的風險。

In the years ahead, we hope to move much of our excess liquidity into businesses that Berkshire will permanently own. The immediate prospects for that, however, are not good: Prices are sky-high for businesses possessing decent long-term prospects.

在接下來的幾年裡,我們希望將很大一部分的過剩流動性轉移到波克夏將會永久保有的業務中去。然而,就此而言其近期前景並不好:那些擁有良好長期前景的企業的價格高得離譜。

That disappointing reality means that 2019 will likely see us again expanding our holdings of marketable equities. We continue, nevertheless, to hope for an elephant-sized acquisition. Even at our ages of 88 and 95 – I’m the young one – that prospect is what causes my heart and Charlie’s to beat faster. (Just writing about the possibility of a huge purchase has caused my pulse rate to soar.)

這種令人失望的現實情況意味著,我們很可能會在2019年中再次擴大對有價證券的持有量。儘管如此,我們仍舊希望能夠達成一項“大象”級別的並購交易。儘管我們兩人都已是88歲和95歲高齡——我是兩人當中比較年輕的那個——但這種前景仍舊會讓我和查理心跳加快。(剛寫到進行一筆巨額並購交易的可能性,我的脈搏就飆升了。)

My expectation of more stock purchases is not a market call. Charlie and I have no idea as to how stocks will behave next week or next year. Predictions of that sort have never been a part of our activities. Our thinking, rather, is focused on calculating whether a portion of an attractive business is worth more than its market price.

我的預期是未來將會購買更多的股票,但這並不是市場決定的結果。查理和我對股市下周或明年的走勢毫無概念,這種預測從來都不是我們會從事的活動。相反,我們的想法是專注於計算一家有吸引力的企業的一部分股票是否會比其市場價格更值錢。

************

I believe Berkshire’s intrinsic value can be approximated by summing the values of our four asset-laden groves and then subtracting an appropriate amount for taxes eventually payable on the sale of marketable securities.

我認為,計算波克夏的內在價值的大致方式是,將我們四個豐裕的資產類別的價值加到一起,然後減去出售有價證券所應繳納的稅款的適當金額。

You may ask whether an allowance should not also be made for the major tax costs Berkshire would incur if we were to sell certain of our wholly-owned businesses. Forget that thought: It would be foolish for us to sell any of our wonderful companies even if no tax would be payable on its sale. Truly good businesses are exceptionally hard to find. Selling any you are lucky enough to own makes no sense at all.

你們可能會問,如果我們出售特定的全資企業,那麽波克夏將需承擔的主要稅收成本是否也不該得到稅收抵免。忘記那種想法吧:如果我們賣掉任何一家優秀的公司,那都是很是愚蠢的,即使賣出這些公司並不需要繳稅。真正的好企業是特別難找的,出售任何你足夠幸運才得以擁有的東西是講不通的。

The interest cost on all of our debt has been deducted as an expense in calculating the earnings at Berkshire’s non-insurance businesses. Beyond that, much of our ownership of the first four groves is financed by funds generated from Berkshire’s fifth grove – a collection of exceptional insurance companies. We call those funds “float,” a source of financing that we expect to be cost-free – or maybe even better than that – over time. We will explain the characteristics of float later in this letter.

在計算波克夏非保險業務的收益時,所有債務的利息成本都已被扣除。另外,我們對前四個資產類別的大部分所有權都是由波克夏的第五個資產類別——一批優秀的保險公司——來提供資金的。我們將這些資金稱為“浮存金”,並期望隨著時間的推移,這種資金將是無成本的——或是可能比這更好。我們將在這封信的稍後部分解釋浮存金的特點。

最後,很關鍵而且長久以來都很重要的一點是:通過將五個資產類別合並成一個整體的方式,波克夏的價值被最大化了。這種安排使我們能夠無縫地、客觀地分配大量資本,消除企業風險,避免孤立,以極低的成本為資產提供資金,偶爾利用一下稅收效率,並將管理費用降至最低水準。

At Berkshire, the whole is greater – considerably greater – than the sum of the parts.

在波克夏,整體要大於——是遠遠大於——各個部分的簡單相加。

Repurchases and Reporting

回購和報告

Earlier I mentioned that Berkshire will from time to time be repurchasing its own stock. Assuming that we buy at a discount to Berkshire’s intrinsic value – which certainly will be our intention – repurchases will benefit both those shareholders leaving the company and those who stay

此前我曾提到,波克夏將不時回購自己的股票。假設我們以低於波克夏內在價值的價格購買股票——我們的意圖當然是這樣的——那麽回購對那些離開公司的股東和留下來的股東都將是有利的。

True, the upside from repurchases is very slight for those who are leaving. That’s because careful buying by us will minimize any impact on Berkshire’s stock price. Nevertheless, there is some benefit to sellers in having an extra buyer in the market.

誠然,回購的好處對於那些將要離開的人來說是微乎其微的。這是因為,我們謹慎的回購活動將在最大限度上降低對波克夏股價的任何影響。但對賣家來說,在市場上多出一個買家是有一些好處的。

For continuing shareholders, the advantage is obvious: If the market prices a departing partner’s interest at, say, 90¢ on the dollar, continuing shareholders reap an increase in per-share intrinsic value with every repurchase by the company. Obviously, repurchases should be price-sensitive: Blindly buying an overpriced stock is valuedestructive, a fact lost on many promotional or ever-optimistic CEOs.

對於繼續留下來的股東來說,好處是顯而易見的:比如說,如果市場將離開的合夥人的權益定價為每美元90美分,那麽對繼續留下來的股東來說,每股內在價值就會隨著公司的每一次回購而增長。顯然,回購應該是具有價格敏感性的:盲目購買定價過高的股票對價值具有破壞性,很多做推廣的或是永遠樂觀的首席執行官都漏掉了這個事實。

When a company says that it contemplates repurchases, it’s vital that all shareholder-partners be given the information they need to make an intelligent estimate of value. Providing that information is what Charlie and I try to do in this report. We do not want a partner to sell shares back to the company because he or she has been misled or inadequately informed.

當一家公司稱其打算回購股票時,至關重要的一點是要向所有股東合夥人提供其所需要的資訊,以便他們對價值做出明智的估測,而提供這些資訊是查理和我在這份報告中試圖要做的事情。我們不希望合作夥伴向公司賣回股票,只是因為他/她受到了誤導,或是沒能獲得充足的資訊。

Some sellers, however, may disagree with our calculation of value and others may have found investments that they consider more attractive than Berkshire shares. Some of that second group will be right: There are unquestionably many stocks that will deliver far greater gains than ours.

但是,有些賣家可能不同意我們的價值計算,另一些人則可能已經找到了他們認為比波克夏股票更具吸引力的投資。在第二批人中,有些人將是正確的:毫無疑問,有許多股票都將帶來比我們的股票更大的收益。

In addition, certain shareholders will simply decide it’s time for them or their families to become net consumers rather than continuing to build capital. Charlie and I have no current interest in joining that group. Perhaps we will become big spenders in our old age.

另外,某些股東會簡單地判定,現在已經到了他們或其家人該要成為淨消費者、而不是繼續積累資本的時候。查理和我現在沒有興趣加入那個群體,或許要到我們年老的時候,才會成為大手大腳的人吧。

************

For 54 years our managerial decisions at Berkshire have been made from the viewpoint of the shareholders who are staying, not those who are leaving. Consequently, Charlie and I have never focused on current-quarter results.

54年以來,我們在波克夏作出的管理決策一直都是從留下來的股東、而不是那些離開的股東的角度出發的。因此,查理和我從來都不會把關注的重點放在本季度的業績上。

Berkshire, in fact, may be the only company in the Fortune 500 that does not prepare monthly earnings reports or balance sheets. I, of course, regularly view the monthly financial reports of most subsidiaries. But Charlie and I learn of Berkshire’s overall earnings and financial position only on a quarterly basis.

事實上,波克夏可能是《財富》雜誌500強中唯一不編制月度盈利報告或資產負債表的公司。當然,我經常都會查看多數子公司的月度財務報告。但對於波克夏的總體收益和財務狀況,查理和我只會通過季度報告來加以瞭解。

Furthermore, Berkshire has no company-wide budget (though many of our subsidiaries find one useful). Our lack of such an instrument means that the parent company has never had a quarterly “number” to hit. Shunning the use of this bogey sends an important message to our many managers, reinforcing the culture we prize.

此外,波克夏不會針對整個公司制定預算(但許多子公司都發現制定預算是有用的)。我們缺少這樣的工具,這就意味著母公司從來都沒有一個季度“數字”需要去實現。避免制定這種令人恐懼的目標向我們的許多經理人傳遞了一個重要的資訊,加強了我們所珍視的文化。

Over the years, Charlie and I have seen all sorts of bad corporate behavior, both accounting and operational, induced by the desire of management to meet Wall Street expectations. What starts as an “innocent” fudge in order to not disappoint “the Street” – say, trade-loading at quarter-end, turning a blind eye to rising insurance losses, or drawing down a “cookie-jar” reserve – can become the first step toward full-fledged fraud. Playing with the numbers “just this once” may well be the CEO’s intent; it’s seldom the end result. And if it’s okay for the boss to cheat a little, it’s easy for subordinates to rationalize similar behavior.

多年以來,查理和我已經看到了各式各樣的不良企業行為——有會計方面的,也有運營方面的——都是由於管理層希望達到華爾街預期而引發的。為了不讓“華爾街”失望,有些公司最初原本只是想要“無害”地弄虛作假——比如說,在季度末時超載交易,對保險損失的成本視而不見,或是掏空“餅乾罐”儲備等——但這可能會成為全面欺詐的第一步。首席執行官的意圖可能是“僅此一次”給數據注水,但最終的結果少有與其最初意圖相符的。如果說高層小小作弊是無傷大雅的,那麽下屬就很容易將類似的行為合理化。

At Berkshire, our audience is neither analysts nor commentators: Charlie and I are working for our shareholder-partners. The numbers that flow up to us will be the ones we send on to you.

在波克夏,我們的閱聽人既不是分析師,也不是評論人士:查理和我是效命於我們的股東合作夥伴的。我們從下屬那裡獲得的數據,就是我們發給你們的數據。

Non-Insurance Operations – From Lollipops to Locomotives

非保險業務 - 從棒棒糖到機車

Let’s now look further at Berkshire’s most valuable grove – our collection of non-insurance businesses – keeping in mind that we do not wish to unnecessarily hand our competitors information that might be useful to them. Additional details about individual operations can be found on pages K-5 – K-22 and pages K-40 – K-51.

作為一個集團,這些企業在2018年的稅前淨利潤為208億美元,比2017年增長24%。我們在2018年的收購隻帶來了微不足道的收益。

I will stick with pre-tax figures in this discussion. But our after-tax gain in 2018 from these businesses was far greater – 47% – thanks in large part to the cut in the corporate tax rate that became effective at the beginning of that year. Let’s look at why the impact was so dramatic.

在此的討論中,我會堅持用稅前數字。 但是,我們2018年從這些業務中獲得的稅後收益的漲幅要遠高於稅前,高達47% - 這在很大程度上要歸功於年初生效的公司稅率消減。讓我們來看看為什麽影響如此戲劇性。

Begin with an economic reality: Like it or not, the U.S. Government “owns” an interest in Berkshire’s earnings of a size determined by Congress. In effect, our country’s Treasury Department holds a special class of our stock – call this holding the AA shares – that receives large “dividends” (that is, tax payments) from Berkshire. In 2017, as in many years before, the corporate tax rate was 35%, which meant that the Treasury was doing very well with its AA shares. Indeed, the Treasury’s “stock,” which was paying nothing when we took over in 1965, had evolved into a holding that delivered billions of dollars annually to the federal government. 從經濟現實開始:無論喜歡與否,美國政府“擁有”伯克希爾的一部分權益,其比例由國會決定。 實際上,我們國家的財政部持有我們一種特殊類別的股票 - 稱之為持有AA股票 - 並從伯克希爾獲得大量“股息”(即稅收)。 2017年,與多年前一樣,企業稅率為35%,這意味著財政部的AA股表現非常好。 事實上,財政部在我們1965年接手伯克希爾時沒有支付任何費用的“股票”,在過去幾十年裡已經發展成為每年向聯邦政府提供數十億美元的控股權。

Last year, however, 40% of the government’s “ownership” (14/35ths) was returned to Berkshire – free of charge – when the corporate tax rate was reduced to 21%. Consequently, our “A” and “B” shareholders received a major boost in the earnings attributable to their shares.

然而,去年,當公司稅率降至21%時,40%的政府“所有權”(14/35)被免費退還給伯克希爾。 因此,我們的“A”和“B”股東的股票收益大幅增加。

This happening materially increased the intrinsic value of the Berkshire shares you and I own. The same dynamic, moreover, enhanced the intrinsic value of almost all of the stocks Berkshire holds.

這種情況實質上增加了你和我擁有的波克夏股票的內在價值。此外,同樣的因素還增加了伯克希爾幾乎所有持股的內在價值。

這些是關鍵因素。但還有其他一些因素使得我們的收益受到不利影響。例如,我們的大型公用事業運營所帶來的稅收優惠需要傳遞給客戶。同時,適用於我們從國內公司獲得的大量股息的稅率幾乎沒有變化,約為13%。 (這種較低的利率一直是合乎邏輯的,因為我們的被投資者已經為他們向我們支付股息的利潤交過稅了。)但總的來說,新法律使我們的業務和我們擁有的股票更有價值。

Which suggests that we return to the performance of our non-insurance businesses. Our two towering redwoods in this grove are BNSF and Berkshire Hathaway Energy (90.9% owned). Combined, they earned $9.3 billion before tax last year, up 6% from 2017. You can read more about these businesses on pages K-5 – K-10 and pages K-40 – K-45.

這表明我們恢復了非保險業務的表現。我們在這個樹林裡的兩個高聳的紅杉是BNSF和Berkshire Hathaway Energy(擁有90.9%)。合並之後,他們去年的稅前利潤為93億美元,比2017年增長了6%。您可以在K-5-K-10頁和K-40-K-45頁上閱讀更多關於這些業務的信息。

Our next five non-insurance subsidiaries, as ranked by earnings (but presented here alphabetically), Clayton Homes, International Metalworking, Lubrizol, Marmon and Precision Castparts, had aggregate pre-tax income in 2018 of $6.4 billion, up from the $5.5 billion these companies earned in 2017.

我們接下來的按收益排名靠前的五家非保險子公司(這裡按字母順序排列)分別為:Clayton Homes,International Metalworking,Lubrizol,Marmon和Precision Castparts,他們在2018年的稅前利潤總額為64億美元,高於在2017年獲得的55億美元。

The next five, similarly ranked and listed (Forest River, Johns Manville, MiTek, Shaw and TTI) earned $2.4 billion pre-tax last year, up from $2.1 billion in 2017.

再接下來的五家公司(Forest River,Johns Manville,MiTek,Shaw和TTI)去年的稅前利潤為24億美元,高於2017年的21億美元。

The remaining non-insurance businesses that Berkshire owns – and there are many – had pre-tax income of $3.6 billion in 2018 vs. $3.3 billion in 2017.

波克夏擁有的剩餘非保險業務 - 有許多 - 在2018年的稅前利潤為36億美元,而2017年為33億美元。

Insurance, “Float,” and the Funding of Berkshire

保險,“浮存金“和波克夏的資金

Our property/casualty (“P/C”) insurance business – our fifth grove – has been the engine propelling Berkshire’s growth since 1967, the year we acquired National Indemnity and its sister company, National Fire & Marine, for $8.6 million. Today, National Indemnity is the largest property/casualty company in the world as measured by net worth.

1967年以來,財產/意外險(P / C)業務 – 第五大收益來源 – 一直是波克夏業績增長的引擎。1967年,波克夏以860萬美元收購了國民保險公司(National Indemnity)及其姊妹公司國民火災及海事保險公司(National Fire&Marine)。如今,以淨資產衡量,國民保險公司是世界上最大的財產/意外險公司。

One reason we were attracted to the P/C business was the industry’s business model: P/C insurers receive premiums upfront and pay claims later. In extreme cases, such as claims arising from exposure to asbestos, or severe workplace accidents, payments can stretch over many decades.

我們被P / C業務吸引的原因之一是該行業的商業模式:P / C保險公司先收取保費後賠付。在極端情況下,一些理賠(如接觸石棉,或嚴重的工作場所事故)的賠付可能持續數十年。

This collect-now, pay-later model leaves P/C companies holding large sums – money we call “float” – that will eventually go to others. Meanwhile, insurers get to invest this float for their own benefit. Though individual policies and claims come and go, the amount of float an insurer holds usually remains fairly stable in relation to premium volume. Consequently, as our business grows, so does our float. And how it has grown, as the following table shows:

這種“先收取保費,後賠付”的模式讓P / C公司持有大筆資金 - 我們稱之為“浮存金” - 最終會賠付給其他人。與此同時,保險公司會將這筆浮存金拿去投資獲利。雖然個人的保單和理賠來來去去,但保險公司持有的保費收入相關的浮存金一般較為穩定。因此,隨著保險業務的增長,浮存金也隨之增長。下表所示為浮存金的具體增長情況:

* Includes float arising from life, annuity and health insurance businesses.

* 包括人壽、年金和健康保險業務獲得的浮存金。

We may in time experience a decline in float. If so, the decline will be very gradual – at the outside no more than 3% in any year. The nature of our insurance contracts is such that we can never be subject to immediate or nearterm demands for sums that are of significance to our cash resources. That structure is by design and is a key component in the unequaled financial strength of our insurance companies. That strength will never be compromised.

我們偶爾也會遇到浮存金回落。如果浮存出現下滑,下滑幅度將是非常緩慢的 - 單一年度最多不超過3%。我們的保險合約的性質使我們永遠不會受到對我們現金資源具有重要意義的金額的即時或近期需求。這種結構是精心設計的,是我們保險公司無與倫比的財力的關鍵組成部分。這方面能力的絕不會妥協。

If our premiums exceed the total of our expenses and eventual losses, our insurance operation registers an underwriting profit that adds to the investment income the float produces. When such a profit is earned, we enjoy the use of free money – and, better yet, get paid for holding it.

如果保費超過我們的支出和最終損失,我們的保險業務會獲得承保利潤,進一步增加浮存的投資收益。獲得承保利潤時,我們有自由資金可用 - 而且,更好的是,通過持有這筆資金獲得回報。

Unfortunately, the wish of all insurers to achieve this happy result creates intense competition, so vigorous indeed that it sometimes causes the P/C industry as a whole to operate at a significant underwriting loss. That loss, in effect, is what the industry pays to hold its float. Competitive dynamics almost guarantee that the insurance industry, despite the float income all its companies enjoy, will continue its dismal record of earning subnormal returns on tangible net worth as compared to other American businesses.

不幸的是,所有保險公司都希望實現這一圓滿結果,進而導致競爭激烈,以至於整個P / C行業處於嚴重的承保虧損狀態。實際上,這種損失是整個行業為持有浮存而付出的代價。儘管所有公司都能享有浮存收益,與美國的其他行業相比,持續的競爭幾乎鐵定讓保險行業繼續面臨有形淨資產收益低於正常水準的慘淡記錄。

Nevertheless, I like our own prospects. Berkshire’s unrivaled financial strength allows us far more flexibility in investing our float than that generally available to P/C companies. The many alternatives available to us are always an advantage and occasionally offer major opportunities. When other insurers are constrained, our choices expand.

不過,我看好波克夏的前景。波克夏擁有無與倫比的財力,這使得我們在投資浮存方面相比其他P / C公司更具靈活性。我們擁有許多選擇始終是一個優勢,這些選擇時不時會帶來重大機遇。當其他保險公司受困,我們的選擇就多了。

Moreover, our P/C companies have an excellent underwriting record. Berkshire has now operated at an underwriting profit for 15 of the past 16 years, the exception being 2017, when our pre-tax loss was $3.2 billion. For the entire 16-year span, our pre-tax gain totaled $27 billion, of which $2 billion was recorded in 2018.

此外,波克夏的P / C公司擁有良好的承保記錄。過去的16年裡,其中15年波克夏都獲得了承保利潤,唯一例外的是2017年,這一年我們的稅前虧損達32億美元。在16年的時間裡,我們的稅前收益總計270億美元,其中去年(2018年)的收益達20億美元。

That record is no accident: Disciplined risk evaluation is the daily focus of our insurance managers, who know that the benefits of float can be drowned by poor underwriting results. All insurers give that message lip service. At Berkshire it is a religion, Old Testament style.

數據記錄並非偶然:嚴格的風險評估是我們的保險經理每天的工作重點,他們深知浮動資金的好處可以抵消不良承保業績。所有保險公司都是給口頭消息。而在波克夏·海瑟威公司,則是一種宗教類似的嚴謹風格。

************

In most cases, the funding of a business comes from two sources – debt and equity. At Berkshire, we have two additional arrows in the quiver to talk about, but let’s first address the conventional components.

在大多數情況下,企業的資金來自兩個來源——債券和股票。在波克夏·海瑟威公司,我們有兩個額外的關鍵值得談論,但讓我們先談談傳統的組成部分。

We use debt sparingly. Many managers, it should be noted, will disagree with this policy, arguing that significant debt juices the returns for equity owners. And these more venturesome CEOs will be right most of the time.

我們對債務非常謹慎。應該注意到的是,很多經理可能不同意這一觀點,認為大量的債務會使股東的回報更加豐厚。而在大多數情況下,這些善於冒險的首席執行官將被證明在多數情況下是正確的。

At rare and unpredictable intervals, however, credit vanishes and debt becomes financially fatal. A Russianroulette equation – usually win, occasionally die – may make financial sense for someone who gets a piece of a company’s upside but does not share in its downside. But that strategy would be madness for Berkshire. Rational people don’t risk what they have and need for what they don’t have and don’t need.

然而,在罕見且不可預測的時間間隔內,信貸消失,債務在財務上變得致命。俄羅斯的輪盤賭等式——通常是贏,偶爾是輸——對於那些從一家公司的上漲中分得一杯羹,但不分享其下跌的人來說,可能具有財務意義。但這種策略對波克夏來說是瘋狂的。理性的人不會拿他們擁有和需要的東西去冒險,去換取他們沒有和不需要的東西。

你們在我們的綜合資產負債表上看到的大部分債務——見K65頁——存在於我們的鐵路和能源子公司,都是重資產型的公司。在經濟衰退期間,這些企業產生的現金流仍然充裕。他們使用的債務既適用於他們的業務,也不受波克夏的擔保。

Our level of equity capital is a different story: Berkshire’s $349 billion is unmatched in corporate America. By retaining all earnings for a very long time, and allowing compound interest to work its magic, we have amassed funds that have enabled us to purchase and develop the valuable groves earlier described. Had we instead followed a 100% payout policy, we would still be working with the $22 million with which we began fiscal 1965.

我們的股本水準則是另一回事:波克夏·海瑟威公司持有的3,490億美元在美國企業界來說是無與倫比的。通過將所有收益長期保留,並允許複利發揮其作用,積累的資金使我們能夠購買和發展前面描述的寶貴的各項業務。如果我們還遵循100%的支付政策,我們仍將只有1965財年開始使用的2200萬美元。

除了使用債務和股本,波克夏·海瑟威公司主要受益於兩種不太常見的企業融資來源。佔比較大的是我所描述的浮動資金。到目前為止,這些資金,儘管它們在我們的資產負債表上被記錄為巨大的淨負債,但他們產生的功效已經超過了同等數量的資金數額所起的作用。這是因為它們通常伴隨著承銷收益。實際上, 多年來,我們一直因為持有和使用所謂的他人的資金而得到報酬。

As I have often done before, I will emphasize that this happy outcome is far from a sure thing: Mistakes in assessing insurance risks can be huge and can take many years to surface. (Think asbestos.) A major catastrophe that will dwarf hurricanes Katrina and Michael will occur – perhaps tomorrow, perhaps many decades from now. “The Big One” may come from a traditional source, such as a hurricane or earthquake, or it may be a total surprise involving, say, a cyber attack having disastrous consequences beyond anything insurers now contemplate. When such a megacatastrophe strikes, we will get our share of the losses and they will be big – very big. Unlike many other insurers, however, we will be looking to add business the next day.

就如我之前做過的,我要強調的是,這一令人高興的結果遠非確定無疑:在評估保險風險方面的錯誤可能是巨大的,可能需要多年之後才能浮出水面。一場將使卡特裡娜颶風和邁克爾颶風相形見絀的大災可能在明天發生,也可能在十年之後發生。“大地震”可能是說傳統意義上額災難,如颶風或地震,或者,它可能完全出乎意料,比如,網絡攻擊造成的災難性後果超出了保險公司目前的預期。當這樣的大災難發生時,我們將分擔損失,而且損失將是巨大的——非常大的。然而,與許多其它保險公司不同的是,我們將在第二天尋求增加業務。

The final funding source – which again Berkshire possesses to an unusual degree – is deferred income taxes. These are liabilities that we will eventually pay but that are meanwhile interest-free.

另一個資金來源——波克夏·海瑟威公司擁有一個不同尋常的優勢——遞延所得稅。這些都是負債,我們最終將支付但無需支付利息。

As I indicated earlier, about $14.7 billion of our $50.5 billion of deferred taxes arises from the unrealized gains in our equity holdings. These liabilities are accrued in our financial statements at the current 21% corporate tax rate but will be paid at the rates prevailing when our investments are sold. Between now and then, we in effect have an interest-free “loan” that allows us to have more money working for us in equities than would otherwise be the case.

像我剛才說的,大約505億美元中的147億美元的的遞延稅收來自股票的未實現收益。這些負債在我們的財務報表中按當前21%的公司稅稅率計算,但將按我們的投資出售時的現行稅率支付。從現在到那時,我們實際上擁有了一筆無息“貸款”,這讓我們能夠有更多的資金為股票投資。

A further $28.3 billion of deferred tax results from our being able to accelerate the depreciation of assets such as plant and equipment in calculating the tax we must currently pay. The front-ended savings in taxes that we record gradually reverse in future years. We regularly purchase additional assets, however. As long as the present tax law prevails, this source of funding should trend upward.

此外,由於我們在計算我們必須繳納的稅款時加速折舊了廠房和設備等資產,因此我們還需要繳納283億美元的遞延所得稅。我們所記錄的前期稅收節省將在未來幾年逐漸好轉。然而,我們還經常購買額外的資產。只要現行稅法持續生效,這一資金來源就應呈上升趨勢。

隨著時間的推移,波克夏的資金(資產負債表的右側一欄)應該會增長,這主要是通過我們所保留的收益來實現的。我們需要通過增加有吸引力的資產,把留存下來的錢很好地用在資產負債表的左側一欄。

GEICO and Tony Nicely

GEICO和托尼-奈斯利(Tony Nicely)

That title says it all: The company and the man are inseparable.

這個標題說明瞭一切:公司的發展和奈斯利是密不可分的。

Tony joined GEICO in 1961 at the age of 18; I met him in the mid-1970s. At that time, GEICO, after a fourdecade record of both rapid growth and outstanding underwriting results, suddenly found itself near bankruptcy. A recently-installed management had grossly underestimated GEICO’s loss costs and consequently underpriced its product. It would take many months until those loss-generating policies on GEICO’s books – there were no less than 2.3 million of them – would expire and could then be repriced. The company’s net worth in the meantime was rapidly approaching zero.

1961年,18歲的托尼加入了GEICO。我在70年代中期見過他。當時,GEICO在經歷了40年的快速增長和出色的承銷業績後,突然發現自己瀕臨破產。該公司最近上任的管理層嚴重低估了GEICO的損失成本,因此低估了其產品的價格。GEICO帳簿上那些產生虧損的保單(數量不少於230萬份)還有好幾個月的時間才能到期,然後才能被重新定價。與此同時,該公司的淨值正迅速趨零。

In 1976, Jack Byrne was brought in as CEO to rescue GEICO. Soon after his arrival, I met him, concluded that he was the perfect man for the job, and began to aggressively buy GEICO shares. Within a few months, Berkshire bought about 1⁄3 of the company, a portion that later grew to roughly 1⁄2 without our spending a dime. That stunning accretion occurred because GEICO, after recovering its health, consistently repurchased its shares. All told, this halfinterest in GEICO cost Berkshire $47 million, about what you might pay today for a trophy apartment in New York.

1976年,傑克-伯恩(Jack Byrne)被任命為首席執行官來拯救GEICO。他上任後不久,我就見到了他。我認為他是這個職位的最佳人選,並開始積極買進GEICO的股票。在幾個月內,波克夏公司購買了該公司約三分之一的股份,後來在沒有增加一分錢投資的情況下,這些資產擴大到了該公司股票份額的二分之一。這種驚人的增長之所以發生,是因為GEICO在恢復健康後,一直在回購股票。總的來說,波克夏花了隻4700萬美元就買下了GEICO二分之一的資產,相當於你今天在紐約買一套豪華公寓的價格。

Let’s now fast-forward 17 years to 1993, when Tony Nicely was promoted to CEO. At that point, GEICO’s reputation and profitability had been restored – but not its growth. Indeed, at yearend 1992 the company had only 1.9 million auto policies on its books, far less than its pre-crisis high. In sales volume among U.S. auto insurers, GEICO then ranked an undistinguished seventh.

現在讓我們回到17年前的1993年,托尼-奈斯利被提升為GEICO的首席執行官(CEO)。那時,GEICO的聲譽和盈利能力得到了恢復,但增長卻沒有恢復。事實上,到1992年底,該公司的汽車保單只有190萬份,遠低於危機前的最高水準。在美國汽車保險公司的銷售量中,GEICO排名第七。

Late in 1995, after Tony had re-energized GEICO, Berkshire made an offer to buy the remaining 50% of the company for $2.3 billion, about 50 times what we had paid for the first half (and people say I never pay up!). Our offer was successful and brought Berkshire a wonderful, but underdeveloped, company and an equally wonderful CEO, who would move GEICO forward beyond my dreams.

1995年末,在托尼重新給GEICO注入活力之後,波克夏提出以23億美元收購GEICO剩餘50%的股份,這大約是我們收購該公司前一半資產價格的50倍(而且人們總說我不會在高位購買資產)。我們的收購獲得了成功,這為波克夏帶來了一家出色且還有發展潛力的公司,以及一位同樣出色的CEO,他讓GEICO的發展超越了我的期望。

GEICO is now America’s Number Two auto insurer, with sales 1,200% greater than it recorded in 1995. Underwriting profits have totaled $15.5 billion (pre-tax) since our purchase, and float available for investment has grown from $2.5 billion to $22.1 billion.

GEICO現在是美國第二大汽車保險公司,銷售額比1995年增長了1200%。自收購以來,該公司的承銷利潤總計為155億美元(稅前),可供投資的流通股市值已從25億美元增至221億美元。

By my estimate, Tony’s management of GEICO has increased Berkshire’s intrinsic value by more than $50 billion. On top of that, he is a model for everything a manager should be, helping his 40,000 associates to identify and polish abilities they didn’t realize they possessed.

據我估計,托尼對GEICO的管理使波克夏的內在價值增加了500多億美元。最重要的是,他是一個管理者的榜樣,他幫助他的4萬名員工發現並發展了自己一直沒有意識到的能力。

Last year, Tony decided to retire as CEO, and on June 30th he turned that position over to Bill Roberts, his long-time partner. I’ve known and watched Bill operate for several decades, and once again Tony made the right move. Tony remains Chairman and will be helpful to GEICO for the rest of his life. He’s incapable of doing less.

去年,托尼決定辭去CEO一職,6月30日,他把這個職位交給了他的長期合作夥伴比爾-羅伯茨(Bill Roberts)。我認識比爾並看著他工作了幾十年,托尼再一次做出了正確的決定。托尼仍然是GEICO的董事長,他的餘生都將是GEICO的得力助手。他不能撒手不管。

All Berkshire shareholders owe Tony their thanks. I head the list.

波克夏的所有股東都應該感謝托尼,尤其是我。

Investments

投資

Below we list our fifteen common stock investments that at yearend had the largest market value. We exclude our Kraft Heinz holding – 325,442,152 shares – because Berkshire is part of a control group and therefore must account for this investment on the “equity” method. On its balance sheet, Berkshire carries its Kraft Heinz holding at a GAAP figure of $13.8 billion, an amount reduced by our share of the large write-off of intangible assets taken by Kraft Heinz in 2018. At yearend, our Kraft Heinz holding had a market value of $14 billion and a cost basis of $9.8 billion.

以下所列出的是截至去年年底我們所持市值最大的前15隻普通股。我們在此排除了卡夫亨氏的持股(325442152股),因為波克夏本身也是一家控股集團,因此必須用“股權”的方法來解釋這筆投資。在波克夏的資產負債表上,我們所持卡夫亨氏的股份按通用會計準則計算為138億美元,這一數字與我們在2018年卡夫亨氏大規模衝銷無形資產時所佔該公司的份額相比有所減少。到去年年底,我們在卡夫亨氏的持股市值為140億美元,成本為98億美元。

* Excludes shares held by pension funds of Berkshire subsidiaries.

* 不包括伯克希爾子公司養老基金持有的股份。

** This is our actual purchase price and also our tax basis.

**這是我們的實際購買價格以及我們的稅基。

Charlie and I do not view the $172.8 billion detailed above as a collection of ticker symbols – a financial dalliance to be terminated because of downgrades by “the Street,” expected Federal Reserve actions, possible political developments, forecasts by economists or whatever else might be the subject du jour.

查理和我都沒有把以上這些股票(總計持股市值1728億美元)當作是精心收集的潛力股。當前這場金融鬧劇將要結束,因為“華爾街”的降級、美聯儲可能採取的行動、可能出現的政治動向、經濟學家的預測,或者其他任何可能成為當前熱門話題的東西,都將終止這場鬧劇。GEICO和托尼-奈斯利(Tony Nicely)

That title says it all: The company and the man are inseparable.

這個標題說明瞭一切:公司的發展和奈斯利是密不可分的。

Tony joined GEICO in 1961 at the age of 18; I met him in the mid-1970s. At that time, GEICO, after a fourdecade record of both rapid growth and outstanding underwriting results, suddenly found itself near bankruptcy. A recently-installed management had grossly underestimated GEICO’s loss costs and consequently underpriced its product. It would take many months until those loss-generating policies on GEICO’s books – there were no less than 2.3 million of them – would expire and could then be repriced. The company’s net worth in the meantime was rapidly approaching zero.

1961年,18歲的托尼加入了GEICO。我在70年代中期見過他。當時,GEICO在經歷了40年的快速增長和出色的承銷業績後,突然發現自己瀕臨破產。該公司最近上任的管理層嚴重低估了GEICO的損失成本,因此低估了其產品的價格。GEICO帳簿上那些產生虧損的保單(數量不少於230萬份)還有好幾個月的時間才能到期,然後才能被重新定價。與此同時,該公司的淨值正迅速趨零。

In 1976, Jack Byrne was brought in as CEO to rescue GEICO. Soon after his arrival, I met him, concluded that he was the perfect man for the job, and began to aggressively buy GEICO shares. Within a few months, Berkshire bought about 1⁄3 of the company, a portion that later grew to roughly 1⁄2 without our spending a dime. That stunning accretion occurred because GEICO, after recovering its health, consistently repurchased its shares. All told, this halfinterest in GEICO cost Berkshire $47 million, about what you might pay today for a trophy apartment in New York.

1976年,傑克-伯恩(Jack Byrne)被任命為首席執行官來拯救GEICO。他上任後不久,我就見到了他。我認為他是這個職位的最佳人選,並開始積極買進GEICO的股票。在幾個月內,波克夏公司購買了該公司約三分之一的股份,後來在沒有增加一分錢投資的情況下,這些資產擴大到了該公司股票份額的二分之一。這種驚人的增長之所以發生,是因為GEICO在恢復健康後,一直在回購股票。總的來說,波克夏花了隻4700萬美元就買下了GEICO二分之一的資產,相當於你今天在紐約買一套豪華公寓的價格。

Let’s now fast-forward 17 years to 1993, when Tony Nicely was promoted to CEO. At that point, GEICO’s reputation and profitability had been restored – but not its growth. Indeed, at yearend 1992 the company had only 1.9 million auto policies on its books, far less than its pre-crisis high. In sales volume among U.S. auto insurers, GEICO then ranked an undistinguished seventh.

現在讓我們回到17年前的1993年,托尼-奈斯利被提升為GEICO的首席執行官(CEO)。那時,GEICO的聲譽和盈利能力得到了恢復,但增長卻沒有恢復。事實上,到1992年底,該公司的汽車保單只有190萬份,遠低於危機前的最高水準。在美國汽車保險公司的銷售量中,GEICO排名第七。

Late in 1995, after Tony had re-energized GEICO, Berkshire made an offer to buy the remaining 50% of the company for $2.3 billion, about 50 times what we had paid for the first half (and people say I never pay up!). Our offer was successful and brought Berkshire a wonderful, but underdeveloped, company and an equally wonderful CEO, who would move GEICO forward beyond my dreams.

1995年末,在托尼重新給GEICO注入活力之後,波克夏提出以23億美元收購GEICO剩餘50%的股份,這大約是我們收購該公司前一半資產價格的50倍(而且人們總說我不會在高位購買資產)。我們的收購獲得了成功,這為波克夏帶來了一家出色且還有發展潛力的公司,以及一位同樣出色的CEO,他讓GEICO的發展超越了我的期望。

GEICO is now America’s Number Two auto insurer, with sales 1,200% greater than it recorded in 1995. Underwriting profits have totaled $15.5 billion (pre-tax) since our purchase, and float available for investment has grown from $2.5 billion to $22.1 billion.

GEICO現在是美國第二大汽車保險公司,銷售額比1995年增長了1200%。自收購以來,該公司的承銷利潤總計為155億美元(稅前),可供投資的流通股市值已從25億美元增至221億美元。

By my estimate, Tony’s management of GEICO has increased Berkshire’s intrinsic value by more than $50 billion. On top of that, he is a model for everything a manager should be, helping his 40,000 associates to identify and polish abilities they didn’t realize they possessed.

據我估計,托尼對GEICO的管理使波克夏的內在價值增加了500多億美元。最重要的是,他是一個管理者的榜樣,他幫助他的4萬名員工發現並發展了自己一直沒有意識到的能力。

Last year, Tony decided to retire as CEO, and on June 30th he turned that position over to Bill Roberts, his long-time partner. I’ve known and watched Bill operate for several decades, and once again Tony made the right move. Tony remains Chairman and will be helpful to GEICO for the rest of his life. He’s incapable of doing less.

去年,托尼決定辭去CEO一職,6月30日,他把這個職位交給了他的長期合作夥伴比爾-羅伯茨(Bill Roberts)。我認識比爾並看著他工作了幾十年,托尼再一次做出了正確的決定。托尼仍然是GEICO的董事長,他的餘生都將是GEICO的得力助手。他不能撒手不管。

All Berkshire shareholders owe Tony their thanks. I head the list.

波克夏的所有股東都應該感謝托尼,尤其是我。

Investments

投資

Below we list our fifteen common stock investments that at yearend had the largest market value. We exclude our Kraft Heinz holding – 325,442,152 shares – because Berkshire is part of a control group and therefore must account for this investment on the “equity” method. On its balance sheet, Berkshire carries its Kraft Heinz holding at a GAAP figure of $13.8 billion, an amount reduced by our share of the large write-off of intangible assets taken by Kraft Heinz in 2018. At yearend, our Kraft Heinz holding had a market value of $14 billion and a cost basis of $9.8 billion.

以下所列出的是截至去年年底我們所持市值最大的前15隻普通股。我們在此排除了卡夫亨氏的持股(325442152股),因為波克夏本身也是一家控股集團,因此必須用“股權”的方法來解釋這筆投資。在波克夏的資產負債表上,我們所持卡夫亨氏的股份按通用會計準則計算為138億美元,這一數字與我們在2018年卡夫亨氏大規模衝銷無形資產時所佔該公司的份額相比有所減少。到去年年底,我們在卡夫亨氏的持股市值為140億美元,成本為98億美元。

* Excludes shares held by pension funds of Berkshire subsidiaries.

* 不包括伯克希爾子公司養老基金持有的股份。

** This is our actual purchase price and also our tax basis.

**這是我們的實際購買價格以及我們的稅基。

Charlie and I do not view the $172.8 billion detailed above as a collection of ticker symbols – a financial dalliance to be terminated because of downgrades by “the Street,” expected Federal Reserve actions, possible political developments, forecasts by economists or whatever else might be the subject du jour.

What we see in our holdings, rather, is an assembly of companies that we partly own and that, on a weighted basis, are earning about 20% on the net tangible equity capital required to run their businesses. These companies, also, earn their profits without employing excessive levels of debt.

相反,我們把這些公司看作是一個我們進行部分持股的集合,而按加權計算,這些公司運營業務所需的有形淨資產淨利約為20%。這些公司也不需要過度舉債就能獲得利潤。

Returns of that order by large, established and understandable businesses are remarkable under any circumstances. They are truly mind-blowing when compared against the return that many investors have accepted on bonds over the last decade – 3% or less on 30-year U.S. Treasury bonds, for example.

在任何情況下,那些規模巨大、成熟且易於理解的企業的訂單回報率都引人矚目。與很多投資者在過去十年接受的債券回報率(比如,30年期美國國債的收益率是3%或更低)相比,其回報率確實令人振奮。

On occasion, a ridiculously-high purchase price for a given stock will cause a splendid business to become a poor investment – if not permanently, at least for a painfully long period. Over time, however, investment performance converges with business performance. And, as I will next spell out, the record of American business has been extraordinary.

有時候,對某隻股票以過高的價格買入會讓一家卓越的企業變成一次糟糕的投資,就算不是永久性的,至少也要痛苦很長一段時間。然而,隨著時間的推移,投資業績與企業業績趨於一致。並且,正如我接下來要闡述的,美國的商業記錄非同尋常。

The American Tailwind

美國經濟的順風車

On March 11th, it will be 77 years since I first invested in an American business. The year was 1942, I was 11, and I went all in, investing $114.75 I had begun accumulating at age six. What I bought was three shares of Cities Service preferred stock. I had become a capitalist, and it felt good.

3月11日將是我第一次投資美國企業的77周年紀念日。1942年,我11歲,我傾盡所有投資114.75美元,這是我從六歲開始積累的資金。我買的是三股城市服務公司(Cities Service)的優先股。我成了一個資本家,感覺很不錯。

Let’s now travel back through the two 77-year periods that preceded my purchase. That leaves us starting in 1788, a year prior to George Washington’s installation as our first president. Could anyone then have imagined what their new country would accomplish in only three 77-year lifetimes?

現在,讓我們回到我購買股票之前的兩個77年的時期。這讓我們從1788年開始,也就是喬治-華盛頓(George Washington)就任美國第一任總統的前一年。那個時候,誰能想像得到他們的新國家會在短短三個77年的歷程中取得什麽樣的成就?

During the two 77-year periods prior to 1942, the United States had grown from four million people – about 1⁄2 of 1% of the world’s population – into the most powerful country on earth. In that spring of 1942, though, it faced a crisis: The U.S. and its allies were suffering heavy losses in a war that we had entered only three months earlier. Bad news arrived daily

在1942年之前的兩個77年的時間裡,美國從一個四百萬人口(約佔全世界人口的0.5%)的國家發展起來,一舉成為全世界最強大的國家。但是,在1942年春,美國面臨了一次危機:美國及其盟國在僅僅三個月前的戰爭中遭受了巨大損失。每天都傳來壞消息。

Despite the alarming headlines, almost all Americans believed on that March 11th that the war would be won. Nor was their optimism limited to that victory. Leaving aside congenital pessimists, Americans believed that their children and generations beyond would live far better lives than they themselves had led.

儘管新聞頭條讓人憂心忡忡,但幾乎所有美國人都堅信在3月11日戰爭將會取得勝利。他們的樂觀態度並不局限於那一次勝利。撇開天生的悲觀主義不談,美國人認為,他們的子女和後代會過上比他們好得多的生活。

The nation’s citizens understood, of course, that the road ahead would not be a smooth ride. It never had been. Early in its history our country was tested by a Civil War that killed 4% of all American males and led President Lincoln to openly ponder whether “a nation so conceived and so dedicated could long endure.” In the 1930s, America suffered through the Great Depression, a punishing period of massive unemployment.

當然,美國民眾知道,未來的路並非一帆風順。從來沒有一帆風順。在建國初期,我們的國家經受了一場內戰的考驗,這場內戰導致4%的美國男性死亡,林肯總統因此公開思考“這樣一個孕育於自由和奉行自由的國家能否長久存在。”在20世紀30年代,美國經歷了大蕭條,一段大規模失業的懲罰性時期。

Nevertheless, in 1942, when I made my purchase, the nation expected post-war growth, a belief that proved to be well-founded. In fact, the nation’s achievements can best be described as breathtaking.

儘管如此,1942年,當我買入股票的時候,國家期望戰後經濟增長,這一信念被證明理由充分。實際上,美國取得的成就可以說是驚人的。

Let’s put numbers to that claim: If my $114.75 had been invested in a no-fee S&P 500 index fund, and all dividends had been reinvested, my stake would have grown to be worth (pre-taxes) $606,811 on January 31, 2019 (the latest data available before the printing of this letter). That is a gain of 5,288 for 1. Meanwhile, a $1 million investment by a tax-free institution of that time – say, a pension fund or college endowment – would have grown to about $5.3 billion.

讓我們拿數字來說話:如果我的114.75美元投資於一個免費的標普500指數基金,並且所有股息進行再投資, 2019年1月31日我的股票價值會增長到(稅前)606,811美元(這封信出版前的最新可得數據)。獲利是5,288倍。同時,當時的一家免稅機構(比方說,養老金基金或大學捐贈基金)的100萬美元投資會增長到約53億美元。

Let me add one additional calculation that I believe will shock you: If that hypothetical institution had paid only 1% of assets annually to various “helpers,” such as investment managers and consultants, its gain would have been cut in half, to $2.65 billion. That’s what happens over 77 years when the 11.8% annual return actually achieved by the S&P 500 is recalculated at a 10.8% rate.

讓我再增加一個我認為會讓你大吃一驚的計算:如果這個假想的機構每年隻向各種“幫助者”支付1%的資產,如投資經理和顧問,那麽其收益會減半,為26.5億美元。當標普500指數實際實現11.8%的年回報率,在按照10.8%的回報率重新計算時,在77年的時間裡就會出現這種情況。

Those who regularly preach doom because of government budget deficits (as I regularly did myself for many years) might note that our country’s national debt has increased roughly 400-fold during the last of my 77-year periods. That’s 40,000%! Suppose you had foreseen this increase and panicked at the prospect of runaway deficits and a worthless currency. To “protect” yourself, you might have eschewed stocks and opted instead to buy 31⁄4 ounces of gold with your $114.75.

那些因政府預算赤字而經常看空美國經濟的人(正如我多年來經常做的那樣)可能會注意到,在我77年職業生涯的最後階段,我國的國債增加了大約400倍。那可是40,000%!假設你已經預見到這種增長,並對失控的赤字和無價值的貨幣前景感到恐慌。為了“保護”自己,你可能已經避開了股票,而是選擇以114.75美元的價格購買31/4盎司的黃金。

And what would that supposed protection have delivered? You would now have an asset worth about $4,200, less than 1% of what would have been realized from a simple unmanaged investment in American business. The magical metal was no match for the American mettle.

但這個保護措施能夠為你帶來什麽呢?假設你現在擁有的資產價值約為4,200美元,採取這種保護性的投資方式所獲得的收益,還不到美國商業中最簡單的非管理投資所能實現資產收益的1%。儘管黃金是一種神奇的金屬,但顯然在資本回報率方面它配不上美國的勇氣。

Our country’s almost unbelievable prosperity has been gained in a bipartisan manner. Since 1942, we have had seven Republican presidents and seven Democrats. In the years they served, the country contended at various times with a long period of viral inflation, a 21% prime rate, several controversial and costly wars, the resignation of a president, a pervasive collapse in home values, a paralyzing financial panic and a host of other problems. All engendered scary headlines; all are now history.

我們國家以兩黨製的方式取得了幾乎令人難以置信的繁榮。自1942年以來,我們共有七位共和黨總統和七位民主黨總統。在這些年裡,美國在不同時期經歷了長期的病毒式通貨膨脹,21%的優惠利率,幾次有爭議以及代價高昂的戰爭,總統辭職,房地產市場崩潰,金融危機癱瘓和許多其他問題。每一個都是一條可怕的頭條新聞;但現在這些已經都成為了歷史。

Christopher Wren, architect of St. Paul’s Cathedral, lies buried within that London church. Near his tomb are posted these words of description (translated from Latin): “If you would seek my monument, look around you.” Those skeptical of America’s economic playbook should heed his message.

聖保羅大教堂的建築師克里斯多夫-雷恩(Christopher Wren)被埋葬在倫敦教堂內。在他的墳墓附近張貼著這些描述性的詞語(翻譯自拉丁語):“如果你想尋找我的紀念碑,請環顧四周。”那些對美國經濟劇本持懷疑態度的人應該留意他的這段話。

In 1788 – to go back to our starting point – there really wasn’t much here except for a small band of ambitious people and an embryonic governing framework aimed at turning their dreams into reality. Today, the Federal Reserve estimates our household wealth at $108 trillion, an amount almost impossible to comprehend.

時間退回到1788年,這是我們的起點,除了一小群雄心勃勃的人和一個旨在將夢想變為現實的管理框架雛形之外,這裡確實什麽都沒有。到今天,美聯儲估計我們的家庭財富為108兆美元,幾乎無法想像。

Remember, earlier in this letter, how I described retained earnings as having been the key to Berkshire’s prosperity? So it has been with America. In the nation’s accounting, the comparable item is labeled “savings.” And save we have. If our forefathers had instead consumed all they produced, there would have been no investment, no productivity gains and no leap in living standards.

請記住,在這封信的前面,我描述的是如何留存收益是波克夏繁榮的關鍵。它一直跟美國的繁榮息息相關。在國家的會計中,可類比的項目應該是“儲蓄”。而且我們保留住了。如果我們的祖先消耗了他們所生產的所有產品,那麽就沒有投資,也就沒有生產力的提高,也沒有生活水準的飛躍。

Charlie and I happily acknowledge that much of Berkshire’s success has simply been a product of what I think should be called The American Tailwind. It is beyond arrogance for American businesses or individuals to boast that they have “done it alone.” The tidy rows of simple white crosses at Normandy should shame those who make such claims.

查理和我樂於承認,波克夏的大部分成功僅僅是搭上了美國經濟發展順風車的結果。對於美國企業或個人而言,吹噓自己“單槍匹馬做到了這一點”已經超越了傲慢。但是在諾曼底的一排排簡單的白色十字架應該讓那些提出這種要求的人感到羞恥。

There are also many other countries around the world that have bright futures. About that, we should rejoice: Americans will be both more prosperous and safer if all nations thrive. At Berkshire, we hope to invest significant sums across borders.

世界上還有許多其他國家都有光明的未來。關於這一點,我們應該感到高興:如果所有國家都能茁壯成長,美國將更加繁榮和安全。對於波克夏來說,我們希望能夠進行大規模的跨境投資。

然而,在接下來的77年裡,我們收入的主要來源幾乎肯定也是依靠搭上美國經濟發展的順風車而獲得。我們很幸運,也很光榮,在我們的背後擁有這股力量。

The Annual Meeting

年會

Berkshire’s 2019 annual meeting will take place on Saturday, May 4th. If you are thinking about attending – and Charlie and I hope you come – check out the details on pages A-2 – A-3. They describe the same schedule we’ve followed for some years.

波克夏2019年年會將於5月4日星期六舉行。如果您正考慮參加,查理和我希望你來(參見第A-2頁和 A-3頁的詳細信息)。這裡描述了我們多年來遵循的相同時間表。

如果您不能參加我們奧馬哈的年會,請通過雅虎的網絡直播參加。Andy Serwer和他的雅虎工作人員在報導整個會議以及採訪美國和國外的許多波克夏經理、名人、金融專家和股東方面做得非常出色。自雅虎加入以來,全世界每年五月的第一個星期六對在奧馬哈發生的事情的瞭解程度已經大大增加。它的報導於上午8:45在CDT開始,並提供國語翻譯。

************

For 54 years, Charlie and I have loved our jobs. Daily, we do what we find interesting, working with people we like and trust. And now our new management structure has made our lives even more enjoyable.

54年來,查理和我都喜歡我們的工作。每天,我們都在做我們感興趣的事情,與我們喜歡和信任的人合作。現在,我們新的管理結構使我們的生活更加愉快。

With the whole ensemble – that is, with Ajit and Greg running operations, a great collection of businesses, a Niagara of cash-generation, a cadre of talented managers and a rock-solid culture – your company is in good shape for whatever the future brings.

也就是說,整個團隊通過Ajit和Greg的運營,實現了業務的擴展並使投資者的現金增值,還擁有一批才華橫溢的管理者和堅如磐石的文化,而這種文化無論如何都能夠使公司處於一個良好的狀態。

英文來源:http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2018ltr.pdf